Ricerca Veloce

Ricerca Avanzata

chiudi

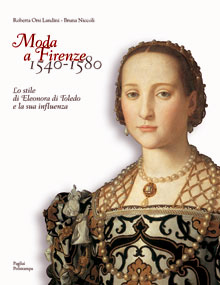

This lavishly illustrated, informative book with a bilingual Italian and English text and footnotes, describes the clothes, textiles, and accessories created for Eleonora, Duchess of Tuscany (1522–62), perhaps best known to many from Bronzino’s portrait o

Moda a Firenze 1540–1580: Lo stile di Eleonora di Toledo e la sua influenza (‘Fashion in Florence 1540–1580: Eleonora of Toledo’s style and its influence’). By Roberta Orsi Landini and Bruna Niccoli, translated by Aelmuire Helen Cleary. Florence: Polistampa, 2005. 254 pp., 120 col. illus. Hbk €58.00. ISBN 88-8304-867-9.This lavishly illustrated, informative book with a bilingual Italian and English text and footnotes, describes the clothes, textiles, and accessories created for Eleonora, Duchess of Tuscany (1522–62), perhaps best known to many from Bronzino’s portrait of her and her son, now in the Uffizi, Florence. Eleonora’s attire, that of her ladies-in-waiting, the records relating to her tailors and embroiderers, her textile suppliers, weavers, hose and bed-jacket knitters, even the nuns who produced her linen smocks, are all discussed. The text is complemented by over a hundred colour reproductions, including portraits of Eleonora and members of her family.

Eleonora Alvarez di Toledo came to Italy at the age of ten when the Emperor Charles V created her father, Don Pedro Alvarez de Toledo, second son of the Duke of Alba, Viceroy of Naples, ruled by Spain since 1504. When she was seventeen, she was married to Cosimo de’ Medici (1519–74), the newly elected Duke of Tuscany who was just twenty years old. They were happily married for twenty-three years, and had eleven children. Eleonora died from malaria, probably exacerbated by tuberculosis, at the young age of forty.

Bruna Niccoli describes the court ceremonial, weddings, baptisms and funerals that provided the context for Eleonora’s wardrobe. For her first public appearance, making her formal entry into Pisa in June 1539 (having travelled by sea from Naples to Livorno, and thence overland to Pisa), Eleonora wore ‘gown of black satin covered with large gold embroideries’ (p. 48). This choice was a visual homage to Charles V, whose wife, Isabella of Portugal, had died in childbirth on 1 May 1539. As Niccoli points out (p. 47 n. 2, and p. 48 n. 10), Duke Cosimo was very sensitive to the political impact of his wedding festivities at such a time, and his bride’s black gown correctly reflected the conventions of international diplomatic protocol and not an apparent Spanish predilection for black (actually worn only for mourning). The following day Eleonora wore a gold-embroidered gown of pavonazzo or purplish-red velvet and she made her formal entry into Florence, where she was married on 29 June 1539, in a gown of crimson satin entirely embroidered with oro battuto (translated as gold lamella). Her hair was covered with a jewelled snood, a Spanish accessory of which she was very fond, worn with drop pearl earrings.

Roberta Orsi Landini discusses Eleonora’s garments which were made from costly and elegant Florentine fabrics and nearly always conformed to Tuscan styling. Their details might imitate aspects of French and German ornamentation but, except for her snoods and jewellery, Eleonora’s attire rarely displayed any Spanish infl uence and, unlike her Spanish contemporaries, she never wore the farthingale (a Spanish invention), which was not adopted in Tuscany until the late 1560s.

Eleonora was fond of clothing, but not extravagant. Approximately seven new sottane or gowns were made annually. She is portrayed in a sottana (translated throughout as a ‘petticoat’) in Bronzino’s famous portrait, and two examples survive: that of white satin in which she was buried in December 1562 (now in the Galleria del Costume, Palazzo Pitti, Florence) and the crimson velvet gown with detachable sleeves (1560) in Pisa (Museo di Palazzo Reale). The sottana always comprised a separate skirt, a bodice with a low square neckline, and detachable sleeves tied with points around the armholes. The sides of the bodice were laced closed at the back, its décolletage covered with an embroidered silk partlet, and embellished in front with applied embroidered guards (bande applicate, translated as ‘bands’), also applied to the trained skirt, in a vertical central strip, and around the hem. A front-buttoning doublet was sometimes worn in place of the bodice. The sottana required around ten metres of silk or woollen fabric and was frequently worn with a zimarra or roba. The zimarra (there is no appropriate English translation) was an ankle-length front fastening ‘coat’ with detachable sleeves, and also decorative false hanging sleeves. It was an indoor, elegantly comfortable over-garment worn open or closed, made in rich fabrics co-ordinating with the sottana, and distinguished by characteristic rows of horizontal frogging and buttons. The similarly ankle-length roba with conventional fastenings and fi xed sleeves was always worn open. Another important outer-garment was the vesta, worn predominantly in winter and requiring ten to sixteen metres of fabric. Its skirt and bodice were joined at the waist by a seam and it had a high neckline opening at the base of the neck, short or long fi xed sleeves, and a trained skirt often split at the front to show off a forepart. Eleonora sometimes wore a jerkin (colletto), a front-fastening, sleeveless garment adopted from contemporary menswear, over the bodice of her vesta, and for extra warmth, stays or a stomach band over her smock or shift. She also owned a pair of red taffeta drawers (or breeches). Drawers are often assumed, erroneously, to have been worn solely by courtesans, but Landini suggests Eleonora may have worn them for extra warmth when riding. More unusual were two steel corsets (p. 131) supplied in February 1549 by an armourer and covered with sky blue taffeta by her tailor. Perhaps these were worn for extra support as she had contracted some form of lung disease in December 1548, possibly tuberculosis, which caused her to lose weight and colour (p. 35).

Eleonora spent more time outdoors than was typical of Tuscan noblewomen, for she was exceptionally fond of riding and hunting, and liked to travel extensively with Cosimo. Her wardrobe thus included a large number of outdoor and travelling clothes. Amongst the more notable items, apart from rain capes of otter skin, were travelling masks that completely protected the face and complexion, and the baviera, a scarf of sorts attached to a hat, which covered the nose and chin. When hunting she wore the Neapolitan pappafico, or cowl hood with attached cape covering the neck and shoulders.

The officials of the ducal wardrobe were not responsible for Eleonora’s jewellery, but did list all her accessories: sable tippets, ostrich feather fans, gloves and muffs, knitted silk hosiery, and footwear. Pianelle, translated as ‘slippers’, but actually mules since they were backless with high wedge heels, were evidently a favourite. In one year Eleonora had thirtyfour pairs made to co-ordinate with various outfits. Most were fairly low, but some were as high as 19 centimetres (7½ inches), making modern Jimmy Choo 5-inch heels seem positively sedate! Worn outdoors, pianelle were often combined with scarpini, the fl at shoes generally worn indoors, and co-ordinated in colour and fabric.

The final chapters discuss the court tailors, embroiderers, and Florentine textile production. Landini notes that Mastro Agostino of Gubbio, who worked as Eleonora’s tailor for thirty years, was paid the same salary as the court painter Agnolo Bronzino (p. 172). Frustratingly, the reader is not told how much. She also describes and illustrates, with extant examples, some of the costly weaves recorded in the surviving Libro di Taglio, the register of (from 1560) textiles entering the ducal household. Fabrics for furnishing and dress were also provided by two weavers who worked specifically for Eleonora at the Pitti Palace — Madonna Francesca di Donato who wove cloth of gold (tessitora sua di drappi d’oro) and her son-in-law. As Landini notes, it was extremely unusual for a woman to weave cloth of gold. They generally produced taffetas and gauzes, since creating heavier silk weaves required greater physical strength.

The three appendices are, unfortunately, untranslated. They contain a transcription of records listing the textiles and trimmings issued for making Eleonora’s garments, an inventory post mortem of Eleonora’s wardrobe donated to the church of San Lorenzo, and another of clothing and other items belonging to duke Cosimo’s second wife Cammilla Martelli (whom he married in 1570), and their daughter Virginia, drawn up on 21 April 1574 following Cosimo’s death. There is an Italian and English glossary and a good bibliography, but no list of illustrations, and no index.

Occasional mistakes in translation should be noted. For example, orlo is translated as ‘hem’ when ‘edge’ is more appropriate: the partlet cannot conceal ‘the upper hem of the smock’ (p. 124); colletto, a jerkin, is often misleadingly translated as ‘collar’. More importantly, rosato (in Florence) always meant ‘scarlet’, not the modern ‘pink’, thus (p. 61) Florentine youths in Rome are described as wearing: ‘pink stockings, trunk hose of crimson velvet, and a doublet of crimson satin with a collar of purplish violet [?] velvet’. This surely should read: ‘scarlet hose, trunk hose of crimson velvet, and a doublet of crimson red satin with a jerkin of purplish-red velvet’.

Occasional lapses into latinate English (p. 57), ‘a very capillary analysis’ (a detailed analysis), and frequent repetitions of the word ‘effectively’ (in fact/indeed), impede easy reading, whilst the omission of the costs of textiles, tailoring and salaries is a little disappointing. Despite these caveats, this is a fascinating and authoritative account, with excellent reproductions, that has a great deal to recommend it. It is well worth purchasing.

Eleonora Alvarez di Toledo came to Italy at the age of ten when the Emperor Charles V created her father, Don Pedro Alvarez de Toledo, second son of the Duke of Alba, Viceroy of Naples, ruled by Spain since 1504. When she was seventeen, she was married to Cosimo de’ Medici (1519–74), the newly elected Duke of Tuscany who was just twenty years old. They were happily married for twenty-three years, and had eleven children. Eleonora died from malaria, probably exacerbated by tuberculosis, at the young age of forty.

Bruna Niccoli describes the court ceremonial, weddings, baptisms and funerals that provided the context for Eleonora’s wardrobe. For her first public appearance, making her formal entry into Pisa in June 1539 (having travelled by sea from Naples to Livorno, and thence overland to Pisa), Eleonora wore ‘gown of black satin covered with large gold embroideries’ (p. 48). This choice was a visual homage to Charles V, whose wife, Isabella of Portugal, had died in childbirth on 1 May 1539. As Niccoli points out (p. 47 n. 2, and p. 48 n. 10), Duke Cosimo was very sensitive to the political impact of his wedding festivities at such a time, and his bride’s black gown correctly reflected the conventions of international diplomatic protocol and not an apparent Spanish predilection for black (actually worn only for mourning). The following day Eleonora wore a gold-embroidered gown of pavonazzo or purplish-red velvet and she made her formal entry into Florence, where she was married on 29 June 1539, in a gown of crimson satin entirely embroidered with oro battuto (translated as gold lamella). Her hair was covered with a jewelled snood, a Spanish accessory of which she was very fond, worn with drop pearl earrings.

Roberta Orsi Landini discusses Eleonora’s garments which were made from costly and elegant Florentine fabrics and nearly always conformed to Tuscan styling. Their details might imitate aspects of French and German ornamentation but, except for her snoods and jewellery, Eleonora’s attire rarely displayed any Spanish infl uence and, unlike her Spanish contemporaries, she never wore the farthingale (a Spanish invention), which was not adopted in Tuscany until the late 1560s.

Eleonora was fond of clothing, but not extravagant. Approximately seven new sottane or gowns were made annually. She is portrayed in a sottana (translated throughout as a ‘petticoat’) in Bronzino’s famous portrait, and two examples survive: that of white satin in which she was buried in December 1562 (now in the Galleria del Costume, Palazzo Pitti, Florence) and the crimson velvet gown with detachable sleeves (1560) in Pisa (Museo di Palazzo Reale). The sottana always comprised a separate skirt, a bodice with a low square neckline, and detachable sleeves tied with points around the armholes. The sides of the bodice were laced closed at the back, its décolletage covered with an embroidered silk partlet, and embellished in front with applied embroidered guards (bande applicate, translated as ‘bands’), also applied to the trained skirt, in a vertical central strip, and around the hem. A front-buttoning doublet was sometimes worn in place of the bodice. The sottana required around ten metres of silk or woollen fabric and was frequently worn with a zimarra or roba. The zimarra (there is no appropriate English translation) was an ankle-length front fastening ‘coat’ with detachable sleeves, and also decorative false hanging sleeves. It was an indoor, elegantly comfortable over-garment worn open or closed, made in rich fabrics co-ordinating with the sottana, and distinguished by characteristic rows of horizontal frogging and buttons. The similarly ankle-length roba with conventional fastenings and fi xed sleeves was always worn open. Another important outer-garment was the vesta, worn predominantly in winter and requiring ten to sixteen metres of fabric. Its skirt and bodice were joined at the waist by a seam and it had a high neckline opening at the base of the neck, short or long fi xed sleeves, and a trained skirt often split at the front to show off a forepart. Eleonora sometimes wore a jerkin (colletto), a front-fastening, sleeveless garment adopted from contemporary menswear, over the bodice of her vesta, and for extra warmth, stays or a stomach band over her smock or shift. She also owned a pair of red taffeta drawers (or breeches). Drawers are often assumed, erroneously, to have been worn solely by courtesans, but Landini suggests Eleonora may have worn them for extra warmth when riding. More unusual were two steel corsets (p. 131) supplied in February 1549 by an armourer and covered with sky blue taffeta by her tailor. Perhaps these were worn for extra support as she had contracted some form of lung disease in December 1548, possibly tuberculosis, which caused her to lose weight and colour (p. 35).

Eleonora spent more time outdoors than was typical of Tuscan noblewomen, for she was exceptionally fond of riding and hunting, and liked to travel extensively with Cosimo. Her wardrobe thus included a large number of outdoor and travelling clothes. Amongst the more notable items, apart from rain capes of otter skin, were travelling masks that completely protected the face and complexion, and the baviera, a scarf of sorts attached to a hat, which covered the nose and chin. When hunting she wore the Neapolitan pappafico, or cowl hood with attached cape covering the neck and shoulders.

The officials of the ducal wardrobe were not responsible for Eleonora’s jewellery, but did list all her accessories: sable tippets, ostrich feather fans, gloves and muffs, knitted silk hosiery, and footwear. Pianelle, translated as ‘slippers’, but actually mules since they were backless with high wedge heels, were evidently a favourite. In one year Eleonora had thirtyfour pairs made to co-ordinate with various outfits. Most were fairly low, but some were as high as 19 centimetres (7½ inches), making modern Jimmy Choo 5-inch heels seem positively sedate! Worn outdoors, pianelle were often combined with scarpini, the fl at shoes generally worn indoors, and co-ordinated in colour and fabric.

The final chapters discuss the court tailors, embroiderers, and Florentine textile production. Landini notes that Mastro Agostino of Gubbio, who worked as Eleonora’s tailor for thirty years, was paid the same salary as the court painter Agnolo Bronzino (p. 172). Frustratingly, the reader is not told how much. She also describes and illustrates, with extant examples, some of the costly weaves recorded in the surviving Libro di Taglio, the register of (from 1560) textiles entering the ducal household. Fabrics for furnishing and dress were also provided by two weavers who worked specifically for Eleonora at the Pitti Palace — Madonna Francesca di Donato who wove cloth of gold (tessitora sua di drappi d’oro) and her son-in-law. As Landini notes, it was extremely unusual for a woman to weave cloth of gold. They generally produced taffetas and gauzes, since creating heavier silk weaves required greater physical strength.

The three appendices are, unfortunately, untranslated. They contain a transcription of records listing the textiles and trimmings issued for making Eleonora’s garments, an inventory post mortem of Eleonora’s wardrobe donated to the church of San Lorenzo, and another of clothing and other items belonging to duke Cosimo’s second wife Cammilla Martelli (whom he married in 1570), and their daughter Virginia, drawn up on 21 April 1574 following Cosimo’s death. There is an Italian and English glossary and a good bibliography, but no list of illustrations, and no index.

Occasional mistakes in translation should be noted. For example, orlo is translated as ‘hem’ when ‘edge’ is more appropriate: the partlet cannot conceal ‘the upper hem of the smock’ (p. 124); colletto, a jerkin, is often misleadingly translated as ‘collar’. More importantly, rosato (in Florence) always meant ‘scarlet’, not the modern ‘pink’, thus (p. 61) Florentine youths in Rome are described as wearing: ‘pink stockings, trunk hose of crimson velvet, and a doublet of crimson satin with a collar of purplish violet [?] velvet’. This surely should read: ‘scarlet hose, trunk hose of crimson velvet, and a doublet of crimson red satin with a jerkin of purplish-red velvet’.

Occasional lapses into latinate English (p. 57), ‘a very capillary analysis’ (a detailed analysis), and frequent repetitions of the word ‘effectively’ (in fact/indeed), impede easy reading, whilst the omission of the costs of textiles, tailoring and salaries is a little disappointing. Despite these caveats, this is a fascinating and authoritative account, with excellent reproductions, that has a great deal to recommend it. It is well worth purchasing.

Data recensione: 01/09/2009

Testata Giornalistica: COSTUME

Autore: Jane Bridgeman